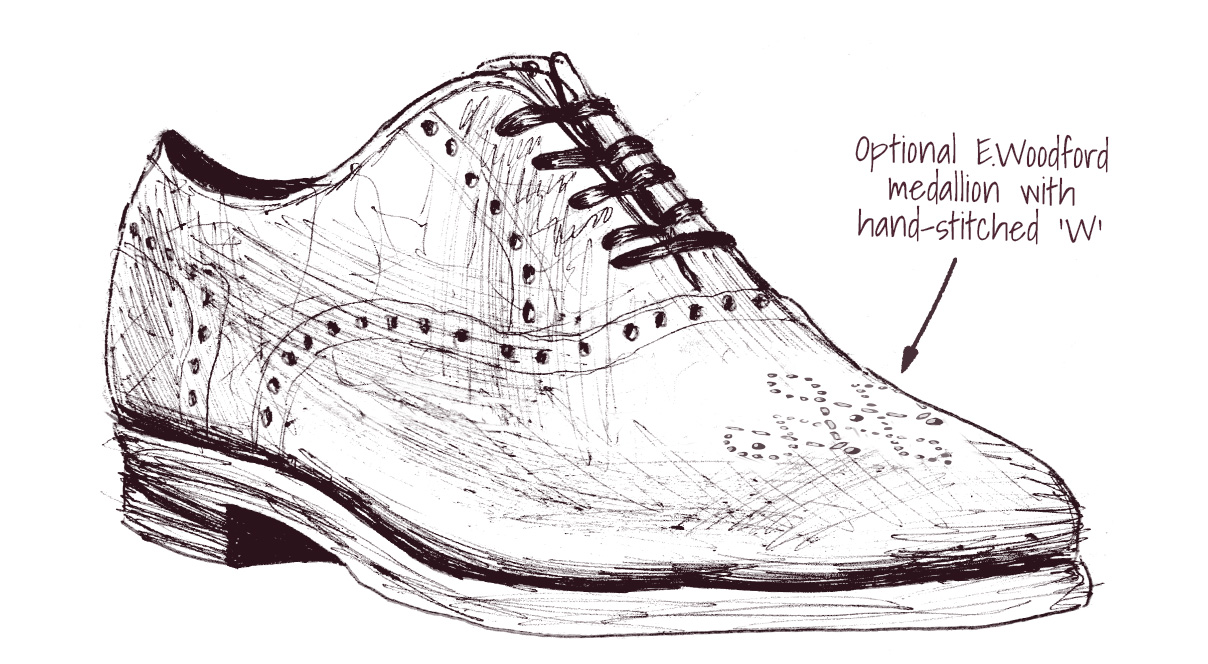

The Oxford is one of the world’s most recognisable pieces of footwear. Traditionally worn as a formal dress shoe, it is defined by its almost plain appearance.

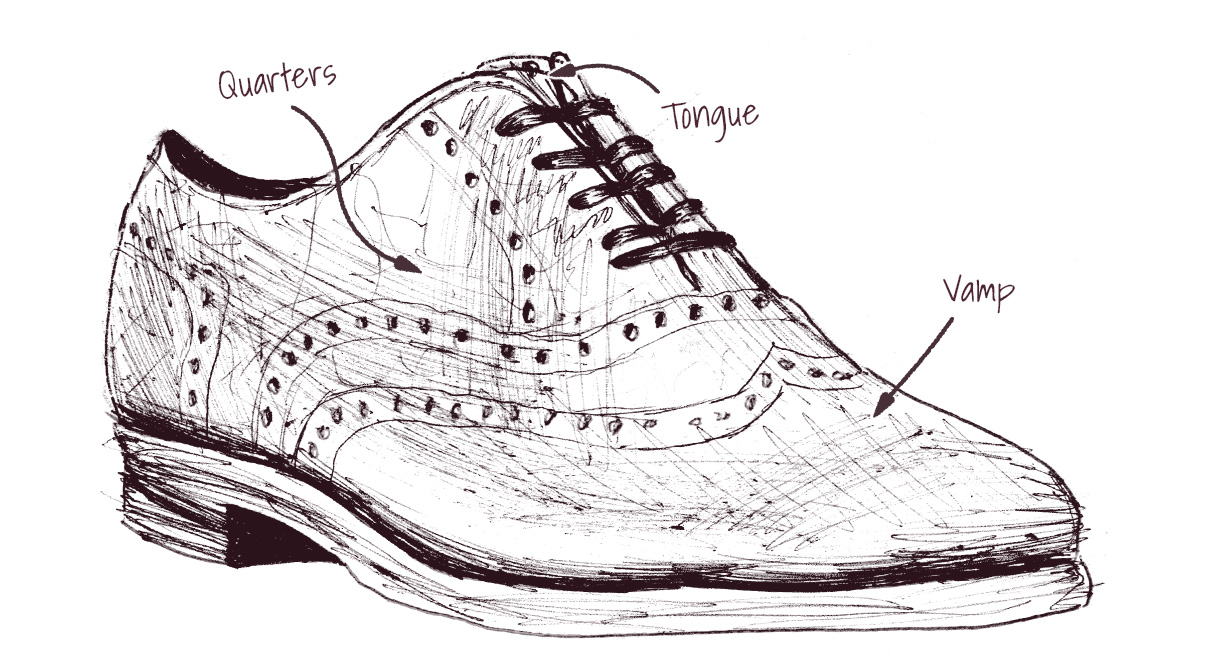

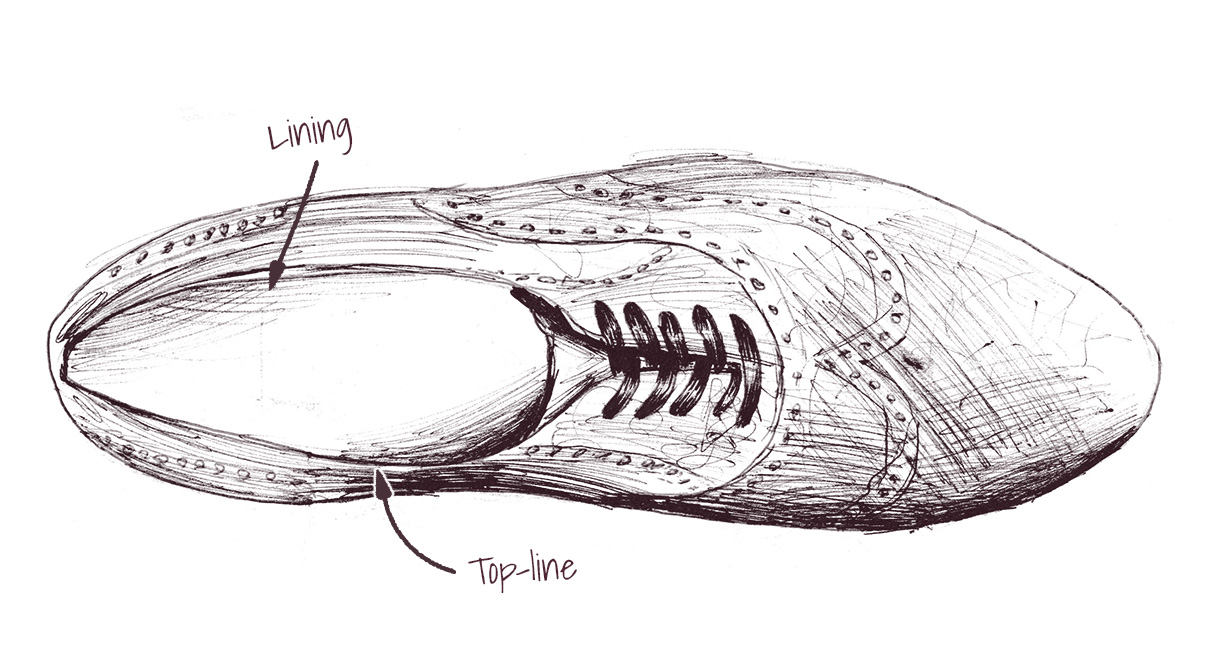

Closed-lacing, with the quarters stitched to the vamp, means little more than the leather and laces are visible from the outside. The upper is held tightly to the foot, as a result, forming a slimmer silhouette, which was historically considered important when wearing a suit.

The shoe sometimes goes under different names: in parts of Ireland, Scotland, and the US, it may be referred to as a Balmoral, after the royal Scottish castle. In France, it’s a Richlieu. While the name can vary, so too can the story of how it came into being.

Probably the most common is that in the late 18th to early 19th century, men – particularly wealthy Oxford University students – were tiring of the discomfort and inconvenience of the tall boots which had domineered fashion for some time. They wanted something comfortable and more casual to distinguish them from older generations.

Styles evolved to meet consumer desires and the cumbersome high-heeled footwear, fastened with side buttons, made way for something less fancy.

For a brief period, an ankle boot known as the Oxonion was popular, but the more modern front-lacing shoe soon became the stylish choice for young men, named after the scholarly English city in which it was first (perhaps) worn.

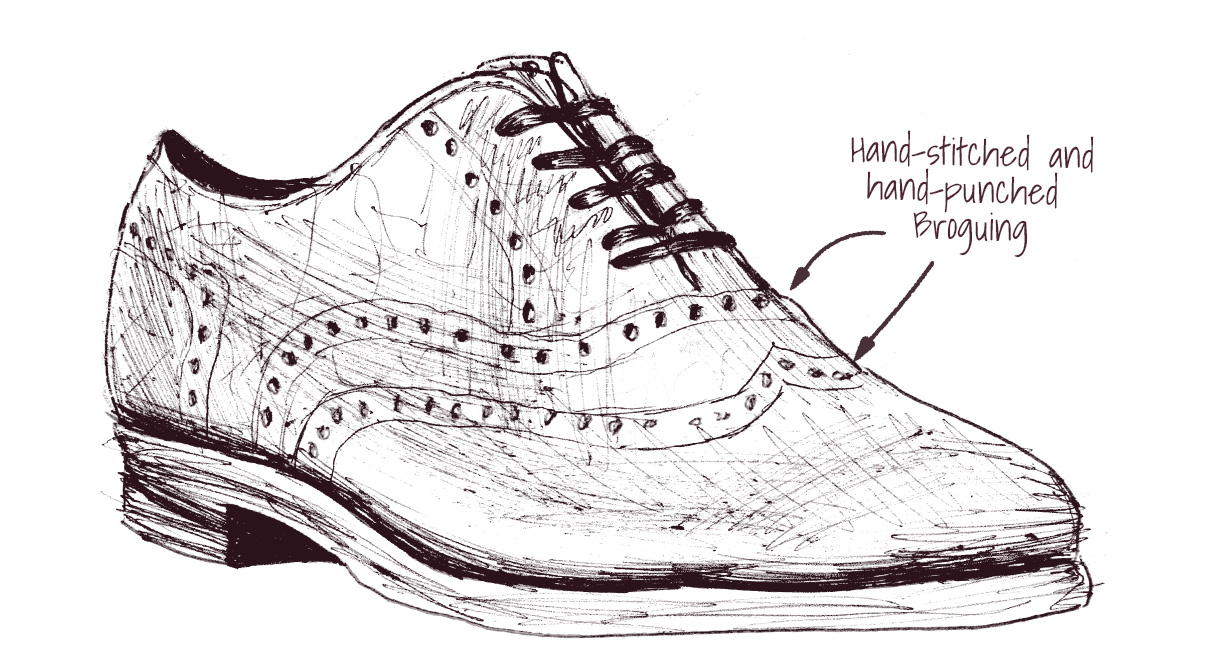

Regardless of the name it takes, a shoe meeting this definition will often feature broguing, a pattern of holes punched into the leather along the toe cap, sides, or upper length of the shoe. This embellishment became particularly popular in around 1890 but, actually, has much earlier roots – evidence suggests Scots and Irish people used it on walking boots in the 1100s.

Back then the holes were functional – designed to allow for water drainage after splashing through damp fields and bogs. While retaining historic resonance brogue patterning today serves as a purely decorative element, be it on an Oxford, a Balmoral, or a Richlieu.